|

PDF

Geneviève Tellier

For more than a decade the British Columbia Select Standing Committee on Finance and Government Services has conducted pre-budget consultations to gather the opinions of groups and individuals on the content of the upcoming provincial budget. Committee members travel to various communities across the province to hear witnesses during public hearings, and to receive submissions (written or video), responses to a survey (sent to every household in the province and available online), as well as letters and emails. At the end of the process, the Committee presents its recommendations to the Legislative Assembly. This article looks at lessons to be drawn from these consultations. It is based upon a survey of some 253 individuals who appeared before the Committee between September 15 and October 15, 2010.

British Columbia is not the only jurisdiction in which such consultations are conducted. The Ontario and federal governments have also adopted provisions to allow legislative committees to conduct pre-budget consultations. However, British Columbia is the only jurisdiction in which there is formal collaboration between the Select Standing Committee and the Ministry of Finance. The Ministry of Finance prepares and distributes the pre-budget documents (including the survey sent to all residents), while the Select Standing Committee receives and deals with the proposals, recommendations and responses submitted by the participants.1 Unlike the Ontario and federal governments, British Columbia’s Ministry of Finance does not conduct its own pre-budget consultations.2

Methodology

There has been much discussion recently about the merits of participatory democracy. Many believe that, by increasing public participation, democratic actors and institutions will regain voters’ confidence. However, there is no consensus on how this would lead to increased confidence. For some, public participation means, first and foremost, that the government should disseminate more information about the decisions it makes. In other words, the government should show more openness and transparency.3 For others, public participation means that the public should be able to convey information to the government. By being attentive to the public, the government can more easily legitimize the decisions it makes.4 Lastly, some argue that public participation should be an exchange of views in the public arena. It is by knowing, discussing and confronting the arguments of others that we will succeed in identifying the best possible solutions to today’s complex problems.5 The mechanisms for public participation can facilitate the flow of information in various directions:

- from the government to the public (openness and transparency);

- from the public to the government (legitimacy of decision-making);

- between the government and the public, and among members of the public (identification of a solution).

It should be noted that these forms of communication are not mutually exclusive; for example, a government may want to be transparent and also to legitimize the choices it makes.

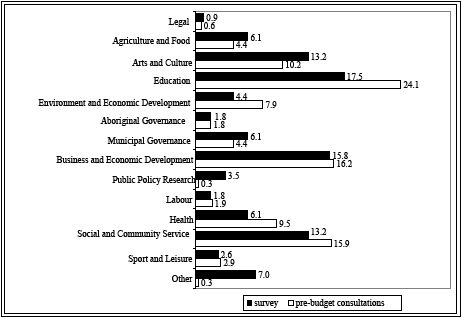

Figure 1 Percentage distribution of survey respondents and total pre-budget consultation participants by sector of activity

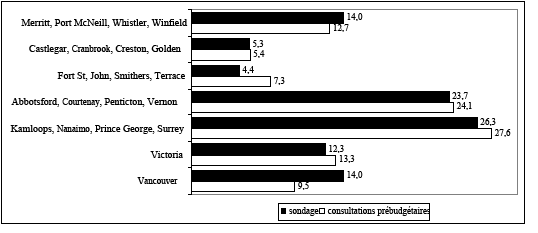

Figure 2 Percentage distribution of survey respondents and total pre-budget consultation participants by location

Table 1: Did the Pre-budget Consultations Inform the Participants about the Government’s Fiscal Policy?

The consultations allowed my organization to be informed about: |

Strongly agree |

Most agree |

Mostly agree |

Strongly agree |

Total |

the province’s budgetary state of affairs (problems, challenges, opportunities) |

5.4% |

27.9% |

46.8% |

19.8% |

100% (n=111) |

budgetary policies under consideration by the government |

6.3% |

31.5% |

45.9% |

16.2% |

100% (n=111) |

initiatives presented in the budget |

8.1% |

28.8% |

40.5% |

22.5% |

100% (n=111) |

We wanted to find out which direction or directions of flow were identified in the pre-budget consultations in British Columbia. To this end, we sought input from consultation participants in order to determine their perceptions and opinions on the subject. Our survey targeted those who had participated in the Committee’s public hearings on Budget 2011.6 During the consultation process, which took place from September 15 to October 15, 2010, the Committee heard 315 individuals who testified on behalf of an organization. We invited the 253 individuals for whom we were able to find a valid email address to take part in our online survey (no paper version). The questionnaire consisted of about twenty multiple-choice questions and one open question that respondents could answer if they wanted to add comments or elaborate on their answers to certain questions (nearly 40% of respondents answered the open question). The survey was conducted between July 13 and August 31, 2011.

A total of 114 questionnaires were completed (8 only partially), which corresponds to a response rate of 45.1%. The respondents seemed fairly representative of the participants in the Budget 2011 consultations. As can be seen in the data presented in Figures 1 and 2, there was very little variation between the distribution of survey respondents and the distribution of the public hearing participants, be it in terms of their sector of activity or location (the education sector seemed somewhat under-represented in our survey but was, nonetheless, the sector with the highest percentage of participants). Moreover, one-third of respondents (33.3%) indicated it was their first time participating in the Committee’s pre-budget consultations, while 12.3% of respondents reported having participated in every pre-budget consultation since the start, that is, ten times. The average for all respondents was four appearances in the last ten years.

Pre-budget consultations as a way for the government to communicate with the public

Are pre-budget consultations an opportunity for participants to find out more about the government’s fiscal policy? Apparently not, according to data collected during our survey. As can be seen in Table 1, one-third of respondents reported that the pre-budget consultations enabled them to be informed about the province’s current budget situation (5.4% of respondents indicated that they strongly agreed with the statement, while 27.9% mostly agreed); 37.8% made this claim regarding the fiscal policies being considered by the government and 36.9% made this claim regarding initiatives presented in the budget.

We can conclude, therefore, that the majority of respondents did not consider themselves to be well informed. These results are somewhat surprising given that the Ministry of Finance prepares and distributes a pre-budget consultation document. One must bear in mind, however, that the consultation paper is a very brief document (usually three pages) containing a few past financial aggregates (such as changes in revenue generated by income tax) and projected aggregates (e.g., economic growth or changes in the province’s debt ratio) and identifying certain issues (clean energy, assistance for families with young children, etc.).

Pre-budget consultations as a way for the public to communicate with government

Pre-budget consultations seem to be most effective in providing organizations with an opportunity to convey their positions to the government. However, the question is not only whether organizations have the opportunity to submit their views and recommendations to the government (this is possible) but also to determine whether the government actually takes note of these proposals. We asked respondents if they felt the Committee members had demonstrated an interest in their organization’s proposals and recommendations. Nearly all of respondents (89.0%) indicated that they strongly agreed (34.5%) or mostly agreed (54.5%) with this statement. (Table 2)

Table 2 Did the Pre-budget Consultations Inform the Government About the Participants’ Opinions?

| |

Strongly agree |

Mostly agree |

Mostly disagree |

Strongly agree |

Total |

The committee members demonstrated interest in my organization’s proposals and recommendations |

34.5% |

54.5% |

6.4% |

4.5% |

100% (n =110) |

MLAs should be informed about the opinion of organizations and individuals regarding budgetary policy |

75.2% |

22.0% |

0.0% |

2.8% |

100% (n =109) |

The Minister of Finance and/or his representatives demonstrated interest in the proposals and recommendations that my organization presented to the committee |

16.5% |

55.0% |

17.4% |

11.0% |

100%(n =109) |

MLAs cannot influence the government’s budgetary policy |

9.2% |

32.1% |

36.7% |

22.0% |

100% (n =109) |

Without these public pre-budgetary consultations my organization would not be able to present its views to the government |

22.9% |

35.8% |

29.4% |

11.9% |

100% (n =109) |

Under parliamentary rules the executive branch of government is responsible for tabling the budget in the Legislative Assembly. This raises the question whether the work of the Committee, a legislative body, actually matters. Here, it seems appropriate to distinguish between what should be done and what is in fact done, that is, between intentions and achievement. Almost all of respondents (97.2%) felt that MLAs should hear from organizations and citizens regarding fiscal policy. The majority of respondents (71.5%) also believe that the Committee’s activities attract the attention of the Ministry of Finance, although a smaller proportion of respondents (58.7%) believe that MLAs can influence the government’s fiscal policy. These differences of opinion can probably be explained by the fact that not all the recommendations presented to the Committee are incorporated by the Ministry of Finance in its budget (more on this point below). In addition, since the Finance Minister and his representatives are not actively involved in the Committee’s activities (the Finance Minister appears before the Committee only to give his own testimony), organizations do not have the opportunity to communicate directly with the Minister. The following comments seem to sum up what many organizations have experienced.

“Although we were provided with the opportunity to present our views, it certainly didn’t seem to have any impact on decisions, so was little more than a sounding board as opposed to an opportunity to make a real case for change.”(Comment 34)

“Senior finance ministry personnel should be present and available to the presenters for questions... also senior finance personnel should be required to respond to all written submissions from registered organizations.” (Comment 23)

Another point that emerged from the survey was that over half of respondents (58.7%) felt that, without these prebudget consultations, they would not be able to present their views on the province’s fiscal policy. Without the Committee consultations, these individuals would have no access or very limited access to the government to present their views. According to some participants:

“It is a difficult process dominated by submissions from organizations requiring funding (not us) but prior to this there was no way to put your views on the record.” (Comment 29)

“Budget/tax policy discussions are undertaken outside of this process. We will use the hearing to publicly articulate and position our recommendations. This is the main feature of the process. We have little expectation the committee will use our recommendations.” (Comment 21)

Pre-budget consultations as a means of discussion and dialogue between the government and the public

The data presented in Table 3 make it possible to determine whether the Committee’s activities also provide an opportunity for participants to discuss and share their views in the public arena. The public hearing format does not leave much room for such dialogue. Each organization was given ten minutes to explain its position, followed by a five-minute question period for the Committee. On average, the Committee heard 22 witnesses per hearing (some hearings had more than 40 witnesses). At the end of each hearing, the public was invited to ask questions to the Committee members or make comments during an “open mic” session. However, very few members of the public did so. Despite this fairly rigid format, almost two-thirds of respondents (65.1%) felt that the consultations allowed them to obtain information regarding the positions of other organizations. However, a larger proportion wanted more interaction. Some 90.8% of respondents felt that the Committee’s pre-budget consultations should seek to facilitate exchanges and dialogue between their organization and members of the Committee and between their organization and other organizations.

Table 3 Are the Pre-budget Consultations Public Participatory Tool?

| |

Strongly agree |

Mostly agree |

Mostly disagree |

Strongly disagree |

Total |

The public pre-budgetary consultations allowed my organization to obtain information regarding the positions of other organizations and individuals. |

11.0% |

54.1% |

26.6% |

8.3% |

100% (n =110) |

The public pre-budgetary consultations should seek to facilitate exchanges and dialogue between my organization and the members of the Committee and between my organization and other organizations and individuals. |

52.3% |

38.5% |

7.3% |

1.8% |

100% (n =109) |

The public pre-budgetary consultations should seek to establish a consensus regarding the budgetary policy that the government should adopt. |

29.4% |

41.3% |

26.6% |

2.8% |

100% (n =109) |

The government should be required to implement the Committee’s recommendations. |

33.9% |

43.1% |

16.5% |

6.4% |

100% (n =109) |

The committee sought to obtain proposals and recommendations that were representative of the opinions of the majority of citizens and organizations of the province. |

17.3% |

58.2% |

20.9% |

3.6% |

100% (n =110) |

The committee sought to obtain proposals and recommendations that were varied and diverse. |

20.0% |

60.9% |

13.6% |

5.5% |

100% (n =110) |

Moreover, the majority of respondents (70.7%) felt that the purpose of the pre-budget consultations was to establish a consensus regarding the fiscal policy that the government should adopt, and that the government should be required to implement the Committee’s recommendations (77.0%). Who should participate in these discussions? About three-quarters of respondents (75.5%) felt that the Committee should seek the opinions of individuals and organizations whose views were representative of the opinions of the majority of the province’s population. A slightly higher proportion (80.9%) felt that the Committee should invite participants with varied and diverse views.

Participants’ overall assessment of the pre-budget consultations

We asked respondents to give their overall assessment of the pre-budget consultation process in British Columbia. The results are provided in Table 4. Overall, nearly two-thirds of respondents (65.1%) reported that they were satisfied with the public consultation process in which they had participated. Only 3.8% said that they did not intend to participate in the next pre-budget consultations (for Budget 2012), although at the time of the survey (two months before the start of the Budget 2012 consultations) more than one in five respondents (22.6%) said they were still undecided. Respondents also seemed satisfied with the Committee’s work. Only one in ten respondents (11.3%) said the Committee’s report did not fairly present their organization’s recommendations. What is surprising, however, is that one-third of respondents (34.0%) seemed unfamiliar with the content of the Committee’s report. Several respondents (17.0%) did not seem to know if the budget tabled following the consultations included measures they had recommended. Nonetheless, 39.6% of respondents indicated that the budget contained measures that matched the recommendations their organization had presented to the Committee.

Table 4 Assessment of thePre-budget Consultation

| |

Yes |

No |

Do not know |

Total |

Overall, are you satisfied with this public pre-budgetary consultation process? |

65.1% |

34.9% |

NA |

100% (n =106) |

Do you intend to participate in the Committee’s public pre-budgetary consultations next year? |

73.6% |

3.8% |

22.6% |

100% (n =106) |

Do you believe that the Committee’s report presented your organization’s proposals and recommendations fairly? |

54.7% |

11.3% |

34.0% |

100% (n =106) |

Did Budget 2011 include measures that match some or all the proposals and recommendations that you presented to the Committee? |

39.6% |

43.4% |

17.0% |

100% (n =106) |

Did the government consider your proposals and recommendations (some or all) inother bills or governmental initiatives? |

39.6% |

60.4% |

NA |

100% (n =106) |

Do you believe that the government will consider your opinion in the coming years? |

69.8% |

30.2% |

NA |

100% (n =106) |

It may seem somewhat surprising that almost three-quarters of respondents indicated that they intended to participate in the pre-budget consultations for Budget 2012, even though not all saw their recommendations included in the Committee’s report or in Budget 2011. This willingness could be explained by the fact that, first, more than one-third of respondents (39.6%) felt their participation in the Budget 2011 pre-budget consultations had already resulted in the government considering their proposals and recommendations in the context of other government initiatives and, second, more than two-thirds of respondents (69.8%) felt that the government would consider their opinion in the coming years.

The participants were also asked whether they felt the Committee had adequate resources to conduct pre-budget consultations. Based on the data in Table 5, more than four out of five respondents felt the Committee could use additional resources. According to the respondents, the Committee should devote more time to public hearings (83.4% of respondents), visit more communities (81.7%), and use new information and communication technologies (ICTs) more effectively (88.9%).

Lastly, several respondents provided additional comments regarding their involvement in the consultation exercise. Although several participants gave a positive evaluation of the Committee’s work, many commented on its limitations. The following comments qualify some of the answers to the survey questions regarding the Committee’s work:

“The best thing about the process was that it engaged us in the conversation. I’m not sure of the effect on the budget, but at least we got to feel we participated.” (Comment 37)

“The idea of the public consultation as an opportunity to hear the views of the people is great, the process seems to be well-executed and from what I’ve seen, the Committee’s report reflects the variety of views presented quite well. Where the process doesn’t work so well is in the execution […] The Consultation would be a lot more meaningful if the government actually implemented the majority of recommendations the Committee arrives at.” (Comment 8)

“While the opportunity to make a presentation to the committee was truly valued and appreciated, it seems that the Committee remained attached to its pre-determined foci and directions when generating the report, and maybe felt limited in capacity to make recommendations divergent from previous Government expressions.” (Comment 13)

Table 5 The Resources at the Committee’s Disposal

The Committee should: |

Strongly agree |

Mostly agree |

Mostly disagree |

Strongly disagree |

Total |

devote more time to public hearings |

28.4% |

55.0% |

14.7% |

1.8% |

100% (n =109) |

visit more communities |

34.9% |

46.8% |

16.5% |

1.8% |

100% (n =109) |

use new information and communication technologies (ICTs) more effectively |

39.4% |

49.5% |

9.2% |

1.8% |

100% (n =109) |

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this survey, what lessons can we draw from British Columbia’s pre-budget consultations? According to the respondents’ overall assessment, most participants seem satisfied with the process used and will continue to participate. In addition, respondents clearly support the idea that MLAs should be informed about the opinions of organizations and individuals regarding the province’s fiscal policy. Such support seems to substantiate the merits of the Committee’s pre-budget consultations.

Nonetheless, the favourable response to the Committee’s work must not obscure the fact that the goal of the consultations is, first and foremost, to encourage organizations and individuals to make recommendations to political representatives (Select Standing Committee on Finance, Ministry of Finance or both) rather than to participate actively in developing the province’s fiscal policy. The exchange of information is essentially unidirectional; that is, it flows from the public to the government. It is surprising that very little information flows in the opposite direction, namely, from the government to the public. One would have thought that the government would want to receive proposals from participants who are well-informed at the outset. This does not seem to be the case.

Does being consulted nevertheless allow participants to have some influence on budget decisions? Several respondents indicated that some of their recommendations had been included in the budget. It is not possible to conclude from this that the participants directly influenced the government’s budgetary decisions. The prebudget consultations may well serve to legitimize certain initiatives that the government was already considering. In other words, participants’ recommendations that appeared in the budget may have been measures already adopted by the government.

The findings of our survey indicate that participants want to be more involved in drawing up the provincial budget. Many respondents wanted to see exchanges among all participants, including MLAs, to establish a consensus. However, trying to achieve a consensus poses certain challenges. First, one must determine who should participate in these discussions. Our survey showed some ambiguity in this regard. Respondents indicated their preference for encouraging the participation of groups that are representative of the majority of the population but will also advance varied and diverse views. These two objectives—representativeness and variety—are not necessarily compatible. Diverse views are often the result of including groups that represent minority or even marginal positions. For the most part, these groups do not represent a majority position, that is, the position of the majority of people.

Furthermore, consensus cannot be achieved without redefining roles in terms of budgetary initiatives. If the Select Standing Committee is mandated to seek a consensus from the community, the government must agree to abandon some of its budgetary responsibilities. Is this kind of power sharing possible when political parties are elected not only to effectively manage provincial affairs, but also to develop initiatives that correspond to their election platform and thus may be very different from initiatives advanced by other parties? In other words, trying to achieve a consensus may not always be an achievable goal when it comes to budgetary initiatives.

It is questionable whether British Columbia’s pre-budget consultation mechanism can combat the cynicism with which many individuals regard public affairs. The fact remains, however, that consultations allow the public to play a more active role in the formulation of the budget. This is a significant change from the old practice of developing budgetary policies in the greatest secrecy. The current problem with the pre-budget consultations is the way in which the public’s recommendations are used. Several respondents said in their comments (some of which were reproduced herein) that they did not know whether the Committee or the Ministry of Finance had considered their recommendations. The rate of participation in British Columbia’s pre-budget consultations has been dropping for the past few years. This trend may be temporary, but it is also possible that a certain degree of weariness has begun to set in among participants who are not seeing compelling results in return for the time and resources they put into the public participation process. This seems to be the biggest challenge facing the Select Standing Committee at this time.

Notes

1. See Kate Ryan-Lloyd, Jonathan Fershau and Josie Schofield, “Pre-budget Consultations in British Columbia”, Canadian Parliamentary Review, Vol. 28, No. 3, autumn, 2005.

2. For additional information on the various pre-budget consultation mechanisms used by the federal and provincial governments, see Geneviève Tellier, “La participation citoyenne au processus d’élaboration des budgets: une analyse des mécanismes instaurés par les gouvernements fédéral et provinciaux canadiens”, Téléscope, 17, 1 (Winter 2011), pp. 95-115

3. Susan Tanaka, «Engaging the Public in National Budgeting: A Non-governmental Perspective», OECD Journal on Budgeting, 7, 2 (November 2007), pp. 139-177.

4. Evert Lindquist, “Citizens, Experts, and Budgets: Evaluating Ottawa’s Emerging Budget Process”, in Susan D. Phillips (ed), How Ottawa Spends, 1994-1995. Making Change, Ottawa, Carleton University Press, 1994, pp. 91-128

5. Yves Sintomer, Carsten Herzberg and Anja Röcke, “Participatory Budgeting in Europe: Potentials and Challenges”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32, 1 (March 2008), pp. 164-178.

6. We focussed on the participants we could easily identify. The identity of witnesses affiliated with an organization that participated in the public hearings (name of the person and his/her organization) appears in the Committee evidence (Hansard) and, in most cases, we were able to find and email address. These are the people we surveyed. The information for participants affiliated with organizations that provided written or videotaped submissions was incomplete (in both cases, the Committee report provided only the names of the organizations, not the name of the person who wrote the brief). The information on those who participated as individuals (by submitting a brief, completing the survey or testifying at public hearings) was also incomplete

|